If you take an interest in the street art scene in the Arab world, you must have heard about Ganzeer. The Guardian described him as a major player in an emerging « counter culture art scene », Al Monitor placed him on a list of 50 people « shaping the culture of the Middle East » and last May the Huffington Post put him on its list of global street artists « shaking up public art ». Last but not least, this month he made the front page of The New York Times Arts & Leisure supplement. At 32 years old, this is a pretty impressive résumé for any budding artist.

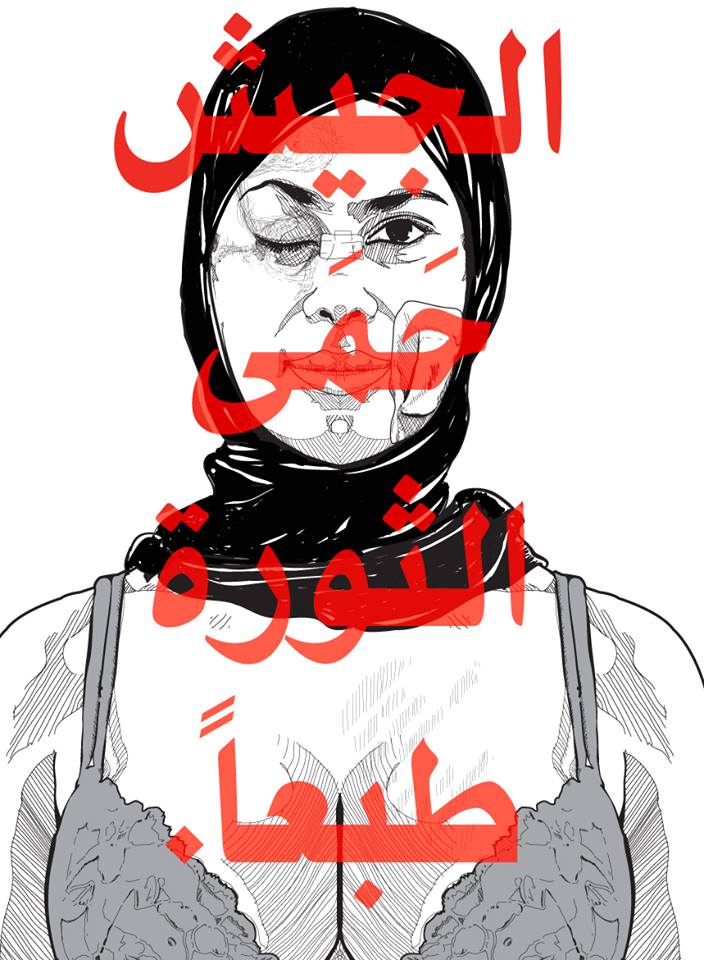

Recently, Mohamed Fahmy -also known as Ganzeer-, was featured in two brilliant works examining the role of graffiti during the Egyptian Revolution, namely Marco Wilms’ documentary Art War and the publication Walls of Freedom by Basma Hamdy and Don Karl. More than three years after Mubarak’s fall, creativity remains prolific. Art is being used more than ever as a weapon to fight against the return of military rule. But today Egyptian street artists are under threat by the new regime.

Indeed, during his TV show Al Raees wal Nass on Friday, May 9th, Ossama Kamal accused Ganzeer of being affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, which equals to calling the artist a terrorist in Egypt today. Needless to say, the organization is banned and most of them are in jail facing death sentences. The Cairene muralist, who has always been critical of both the Brotherhood and the SCAF (Supreme Council of the Armed Forces) in his artwork, has defended his artistic freedom in a statement by retorting Who is afraid of Art?.

To offer you a glimpse into the world of Ganzeer, ONORIENT interviewed the artist. Now, let’s talk about art and revolution with one of the most talented multidisciplinary artists of this generation.

Your artist name is « Ganzeer », which means « chain », how did you pick it?

This was originally the name of a design studio I had set up back in 2005. Although I would have other designers working with me from time to time, it was only just me in this studio, so clients and other people just started to refer to me directly as Ganzeer. And the name sort of caught on and stuck. When I decided to shut down the studio and focus entirely on art-making, I kept the name because it was the one most people knew me by. I had picked it for my design studio in the first place because I thought it was a good metaphor for the role of a designer in society. You see, a ganzeer is typically used to refer to a bicycle chain. Not the chain that locks the bicycle. But the chain that keeps the wheels in motion when pedaling. In a way, that’s what a designer does; we connect ideas.

I know you don’t like to be labeled as a street artist because in some way it reduces your other identities. In fact, you’re also a designer, a comic book artist, you did some installations and videos, you write articles… How do you manage to link these activities?

Well, I just love to experiment and try new things out. It’s completely uninteresting for me to do the same sort of things over and over again. A lot of the time a certain idea I have for a particular topic will require a specific medium with its own set of tools and techniques. And because I have this idea nagging in my brain, I just feel the urge to make it happen, even if I don’t know anything about the medium and its tools. This, for example, is exactly how I ended up doing street art by the way. But I would say that I am first and foremost a designer. In everything I do, whether it’s street art, comic books, or writing, my approach starts from a designer’s perspective.

As an artist, can you tell us how the Revolution has impacted your work? When did you feel the need to express yourself in the street for the first time?

Oh wow. Well, as an artist or designer, I think we all really want to be able to think we can change the world with our work. In the context of a revolution, you definitely want to play a part in the outcome of things. As someone who’s not a particularly skillful protestor or chanter, the skills I could bring to the revolution were obviously in relation to my visual art. When it became obvious that the revolution had not succeeded with the fall of Mubarak, there was an urge to persist to make sure the country was set on a path towards achieving revolutionary hopes and dreams. But I was already out there with my spray paint by January 25th, 2011.

In your art pieces, you tackle a lot of different issues such as corruption or sexual harassment. How do you consider the relation between your art and your activism?

I see myself as an artist much more than as an activist. In fact, I don’t feel comfortable at all within the activist scene. So yeah, I’m an artist, but as an artist I want to create work that is important and has some kind of social impact.

Here we are… Less than one year after the June 30th Revolution, that you have called a coup since the beginning, Egypt has a new president, who is a former field marshal, and many activists are in jail. According to you what will happen next? How do street artists plan to resist military rule when there is a draft law to ban « abusive graffiti »?

Well listen. June 30th was not a revolution for the simple fact that all those millions of people who took to the streets only did it after an announcement by Sisi that the military and police will protect the protestors. In 2011, it was people taking to the street knowing that they may very well get killed and shot by the military and police. So two totally different scenarios; 2011: Revolution, 2013: Orchestrated Coup for sure. In terms of how we can deal with this situation, it’s difficult to answer and figure out. But everyone knows the polls were rigged. People supporting Sisi went to vote and saw how empty the polling stations were. People who boycotted the vote know that they didn’t vote. So both sides know that the announced participation numbers are completely rigged. So the real question is, how will an entire population deal with an illegitimate governing power that blatantly lied to everyone? I foresee inevitable revolution, but one that is nowhere as nice or peaceful as the 2011 uprising.

Your last work is about Islamic pornography. It sounds super haram, doesn’t it? Can you tell us a bit more?

Well the idea of the work is that it is not at all figurative. And that it is very abstract and geometric. While still being undeniably pornographic. So on one hand, it’s not haram at all, because it’s abstract geometric visualizations which according to traditional Islamic teachings is thought to be an acceptable kind of visual art. On the other hand, the pornographic suggestions of the pieces make them very haram. This at the end of the day proves that an art form in and of itself can never be haram or not haram. But haram only exists in some dirty ideas we have in our heads.

Last year you had the opportunity to spend several weeks in Morocco, what were your first impressions? Were you inspired by the country? Did you meet some artists from the underground cultural scene?

Morocco’s an amazing place! I fell in love with it so, so much! The food is scrumptious, the cities are beautiful, amazing craftwork, love the trains and the beaches, love how the chairs of every Salon de Thé is facing the street. I didn’t really meet any artists. I spent most of my time in a house I rented in Meknes’ old Medina, where I locked myself up to write a book (called How to Revolt Cleverly, forthcoming from Dar Al Tanweer). I did meet one lovely designer from Fez though. She saw on my Facebook page that I was in Morocco, so we exchanged messages and she was so nice to show me around her city. From all the conversations I’ve had, I got the sense that people were just so, so nice. I’m pretty sure I’ll be ending up there again at some point.